I don’t know where to begin. They say “the start” is always a good place but if I’m being honest with you, I can’t tell where “my start” starts and where it ends. I’ve put this post off for a long time mostly because I’ve struggled with how to relive those memories and adequately convey the right message about what I went through and the emotions I felt: the fear and doubt; the anxiety and pain; the relief and despair all in one. Mostly, now looking back at that moment, the pictures and the videos, it is amazing to see how far I have come. Consider this part of my cancer journey, as phase two of my treatment. Brace yourselves because this post will be a long one. If you need a bathroom break, some coffee, or five minutes to stretch, now is the time to do it. Are we done yet?

Ok, here goes. When my chemo ended, I had a moment of peace. A month to be exact. Never have I been so relieved in my life. I never wanted that month to end. My body was aching for a break and I can’t say I blame it. For four months straight, it had gone through physical and medical abuse, if I can be honest but it was also going through what was necessary to restore my health and for that, I will always be grateful. Well, in that month (March to be exact), my body yearned for rejuvenation, and my mind yearned for healing. And I indulged. I rested. I meditated. And I tried to survive those damn hot flashes!

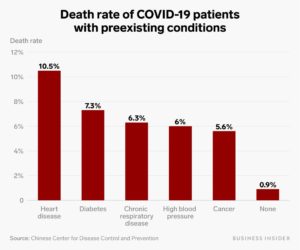

I was happy that for a while, I would not go to the hospital, and have long days of bloodwork, IV’s and chemo. I was relieved that even if temporarily, I would not be in pain for a while. And just when I thought I would finally be able to go out and take a walk, get some air and get my heart rate up, I found out that I would have to be quarantined. Step in COVID. Wow! COVID…. sigh! 2020 sure has been an ‘interesting’ year to say the least. I was relieved that my chemo was over, and suddenly new fears emerged regarding COVID-19, its spread, the details of how it affected those with underlying conditions, and the fatalities. So COVID can increase the fatality rate of cancer patients by up to 5.6 %. according to the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

So I had a mask on, every time I had to step out of the house (mostly to pick up my medications and that was on rare occasions). And thank goodness, the majority of Americans complied. Yet, there was always a concern about ‘exposure’ and feeling immunocompromised and more susceptible to the virus. That entire month, I took precautions and stayed quarantined. For all those who lost loved ones, family, and friends due to the Corona Virus, my heart and prayers go out to you. So March flew by and then April finally came. And yes, phase two of my treatment was about to start. The next step of my treatment was surgery. My interprofessional team of healthcare providers had discussed the details of what would occur to mentally prepare me for the procedure. I was having a radical double mastectomy. A mastectomy is the removal of one breast, and a double (or bilateral) mastectomy is the removal of both. The word ‘radical’ comes in because it involves not only the removal of breast tissue but also adjacent lymph nodes. Have you ever heard of that saying, “easier said than done?” Well, let’s just say nothing I could have ever done would have mentally prepared me for what I was going to experience.

The plan to remove both breasts was decided upon when unusual growths were noticed on the MRI. After the biopsy, it was inconclusive what these were, but my lymph nodes on the left appeared abnormal; this was also on the same side as my affected breast. The doctors figured that to reduce any possibilities of recurrence, it would be a good idea to take off some of the axillary lymph nodes and to remove my other breast. Sometimes, when tumors develop in one breast, there is a very high possibility that the other one will be affected. Furthermore, the proposal to remove the entire breast tissue arose because I had four tumors in one breast alone. There was absolutely no way to try to save any of the breast tissue. In conclusion, my breasts were going to be gutted out. I was completely ok with losing both. To be honest, I would MUCH prefer not to have to go through this again. One thought kept running through my mind: this surgery would greatly reduce the probability of a recurrence or at best, completely eradicate any possibility of breast cancer in the future. After chemotherapy, the tumors shrunk, but they were still there. Take it out. Take it all out, I thought. Get the big, bad tumors out of, and away from me. I’m ready. At least I thought I was.

“You can’t eat anything past midnight the day before. And you can’t have any alcohol as well. And that includes wine. Is that understood?”(Now where have I heard this before? Hhhmmmmm). Anyway, I proudly answered the surgeon, “Are you kidding me? I will give myself a headstart and start fasting at 9 pm!” The doctor chuckled. “I will see you tomorrow then.” “Aye, aye, Captain!” Pre-op was over. I went home, relaxed, and watched a movie. 6 am, my brother Christian and I were up and we were headed to the hospital.

After going through all the Corona Virus protocols and precautions ( mask on, temperature checks, exposure, and travel questions) and changing into my surgical garments, the surgeon came in for one last pep-talk. “We are going to do our best. We are on YOUR side. Though you are mentally prepared for this surgery, we cannot promise what your reaction will be AFTER the surgery. I just want to put that out there. But no matter what emotions you feel, I want you to believe that you will come out of the operating room feeling a great sense of relief that those tumors have been surgically removed.” I assured her, “I’m not worried about that, doc. I’m ready to do this. I can handle it.” Oh boy! Was I wrong! The last thing I remembered after the anesthesia started to set in, were bright lights above my head, and the doctor asking me to count backward… 10, 9, 8, 7, 6… I don’t remember the rest. I was out. And after five hours under the knife, I woke up in the recovery unit.

![]()

![]()

![]()

I was in pain; severe and excruciating pain. My body ached all over and I could barely open my eyes for the first few minutes as I regained consciousness. There was a heaviness in my chest… I looked down and saw that my chest had been tightly bound with a medical corset from my chest through my abdomen. It somewhat restricted my breathing and I remember trying to push the call button to ask the nurse if we could loosen the hold just a little. That was when I realized that I could not move my arms and shoulders. That was also when I realized that there were two tubes on either side of my chest draining blood and residual fluids from the recent surgery. It also dawned on me that I probably needed and wanted something stronger for my pain.

Luckily, the nurse came in a few moments later to check on my incisions and my dressing. She gradually released the hold of my corset and then took off the gauze to examine the incision. This was the first time I was able to see my chest firsthand. I was in so much shock that the initial pain I felt from the actual surgery dissipated and was replaced with sheer horror as I focused on the scars and stitches that ran across the length of my chest. I’m not sure how to explain this part of the narrative. But even as a resilient person and as one who overcomes challenges every day, I have to say that no experience from my past could have prepared me for this one. All I could do was cry. I cried and cried and cried. Slowly at first, then with each breath, I went from moaning to sobbing, to choking, to flat out bursting out in tears. I felt the stream running down my cheeks, and my emotions suddenly went from pain to anger. It was difficult to look at my scars; I felt like I had been robbed… like I had lost a body part and along with it, a part of my soul. I felt like now I understood how the wounded soldier felt after the war. I am not in the military in any shape or form, but if you think about the fact that I am fighting my own battle, that I am fighting through this disease, then by all means that would make me a soldier.

As the nurse wrapped me back up, she whispered words that I have not forgotten to date; words that my friend Sandra has always reminded me of: “Do not be afraid of the storm; You are the storm.” She gave me some morphine, wiped my tears, and told me she would have my “support person” come in and sit with me. Shortly after, Christian and Tim Blocker walked in. You remember Tim, don’t you? He was the one who organized the surprise with the kids for me earlier in the year. He was also the nurse anesthetist during my surgery. “Don’t worry about your scars. Don’t worry about the pain. The essential thing is, the tumors are out, and you have completed another important part of your treatment.” I looked at Tim with hope in my eyes and he looked back at me with encouragement. At that moment, I knew what I wanted to do a video and I already knew what it was that I wanted to say. (Forgive whatever that was on the side of my mouth. I could only have clear liquids so I’m not certain what that was and had to take the word of the nurses who told me I got slightly bruised as I was intubated for surgery. Besides, when you are in so much pain, and right out of the operating room, appearances are the least of your concerns!)

The video says it all so hopefully I don’t have to repeat anything. Just love one another. Just love each other. And most especially, do what you have to do to keep your peace. My parents and close friends called me to check on me because visitors were not allowed in the hospital. Only one person could be inside the hospital at a time, and that person was my cousin, Christian. I was hospitalized for two days, and unfortunately, I was discharged home sooner than was expected because of recent precautions instituted due to COVID. It was not an easy feat, I must say. I was in a lot of pain. I struggled. I was not able to sleep for days. I could not use my upper body so I needed help with my feedings.

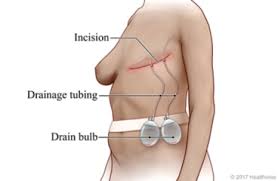

The drains on each side of my breast made sleeping uncomfortable and because they constantly had to be emptied, I did not get more than 3 hours of sleep at a time, if at all. The only thoughts I focused on were, “you are going to get better. You must get better. You are already better.” So it might be hard for you to comprehend what the post-surgical scars look like so I have attached a few images for you to get a better idea.

While mastectomies are an effective means of treating breast cancer, post-surgical treatments can leave a lot of scarring. Besides, most surgeries are dependent on the stage and grade of the tumors. A partial mastectomy (also known as a lumpectomy), involves the removal of the tumor and a perimeter of the surrounding tissue. A great portion of the breast is left intact, and radiation may be required after the surgery. A nipple-sparing mastectomy involves sparing the skin and the areola. Therefore after the surgery, the nipple is still intact.

A total mastectomy involves removal of the breast, areola, nipple, and several lymph nodes if they are biopsied and show signs of cancer. An incision runs across the width of the breast and leaves obvious scar tissue.

A modified radical mastectomy is the procedure where the surgeon removes all the breast tissue, the lymph nodes in the breast, and those in the armpit as well. The difference here is that the chest wall of the patient is left intact. Again, just like the total mastectomy, there is a large visible scar across the chest. I had a bilateral modified radical mastectomy. The drains that were inserted are known as Jackson-Pratt drains. They are essential in removing any residual fluids, including blood that can collect post-surgery. This is to help reduce the risk of infection which may present as a fever, redness, warmth, or a foul and purulent discharge. The insertion point of these drains will also leave visible scars on either side of each breast, similar to the one below. (Image below from Cancer.org)

It is so important to take all antibiotics, muscle relaxants, and pain medications as prescribed. If there is one time I would advise anyone to stay away from exercise, this would be the time. Incisions are still healing and stitches are in place which we do not want to come loose and lead to other complications. You probably shouldn’t be lifting anything greater than 10 lbs. Lots of rest and fluids to replenish those lost after surgery can speed up the healing process and diet, especially proteins, play a major role in recovery. Most importantly, be gentle with yourself. Accept your limitations and ask for help if you need it. So this surgery was a major turning point of my treatment. I had been through chemotherapy and braved that storm. Now, I had just completed the second phase which was the bilateral mastectomy. Somewhere, deep in the crevices of my heart, I knew I never would have made it without God. I had this song on replay as I lay in my recovery room.

You know, a lady at the treatment center where I had my chemotherapy once asked me, “why are cancer patients always so happy?” She was not a patient herself, but her mother was. “It’s just a bit odd to me,” she carried on, “you lose your breasts, your hair, your skin, your nails, your sanity… you have scars that will probably never go away, and your treatments leave you feeling weak, sick, scared and worried about dying. So what exactly are you all always so happy about? Is it for appearances?” This woman was completely right. It dawned on me that all the things she said were true. Initially, I wasn’t sure how to respond. In fact, I wanted to ignore her question altogether. I did not know if she was asking out of curiosity, or out of pain for what her mother was going through. Or maybe it was frustration induced by caregiver strain. But the more I gave it some thought, the more it seemed more apparent to me. “I cannot speak for everyone else, I can only speak for myself; I look forward to each morning, knowing that that day was not guaranteed; that so many people before me, did not survive, but also that so many people before me, did and I want to celebrate the fact that I am still alive, and not allow my illness to define me. I try to live each day intentionally, and to the fullest with the knowledge that if tomorrow was going to be my last day, I wanted to make the best of TODAY.” Now I am not sure if I answered her question, but she did give me something to think about. Cancer patients have some of the worst days ever -but most simply choose to focus on the good ones. Hope is the only thing that gives us courage and reassurance. Tomorrow is not guaranteed for anyone. So no matter how bad it is, smile anyway.

It was hard for me at first… seeing myself this way. Feeling my scars across the width of my chest. Being reminded of what those scars meant and why they were there, to begin with. I felt confused each time I took a shower… it would leave me in a pensive state feeling all the wounds, the incisions, and the scar tissue that were remnants of a very brutal ordeal. I was not sure if I had completely accepted my new circumstance. I would constantly rummage through my thoughts… trying to figure out what I had missed, or what I could have done previously to prevent my current predicament. I had told myself I would be prepared for anything my treatment would throw at me. But nothing can ever prepare you for that, even if you prepare as best you can. I kept thinking to myself, “why did you do this Mabih? Why did I do this? Why did I make this decision? Why me? Why cancer?”

In addition, there is this lack of feeling that is experienced by at least 95% of women who have these surgeries. You lose all sensations in the affected breast (or breasts). So even as I stood in the shower, I could feel the water everywhere on my body, save for my chest. It is the most awkward scenario; I’m not even sure how to explain it. With all that said, I quickly realized over time that these were small prices to pay considering the alternative: chronic illness and possible death. I started to look at my scars as signs of survival; signs of courage, strength, and resilience; signs that I was STILL here; signs that I still had the rest of my life in front of me, and that I was going to make the most of it.

So my advice to you is: if you ever want to take that trip, take it. If you miss someone, call them -even if they don’t call back. If you’ve been too busy at work, don’t forget to hug your spouse and your children when you do come home to them. If you want to start that business, take a leap of faith, and jump right in. If you want to treat or reward yourself, by all means, do. NOW is the time. Most especially, forgive. With that said, forgiveness is hard sometimes, but necessary all the same. Forgive each other. Most importantly, forgive yourself.

Wear your masks, keep six-feet, and stay safe. Looking up to the sun and sending you virtual hugs from across the cosmos.

***Remember, one in eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime. Early detection saves lives.

Love, light, and keeping up this (pink) fight,

Ngumabih

Click here for my next post where I talk about a close friend who was diagnosed with the BRCA1 gene mutation. And yup! You know her too!

You are a true inspiration!

Your story is a true example of the saying “God puts you through what he knows you can handle”

Keep on keeping on 🙏🏾

Thank you dear for letting us into this very difficult and private process in your life. Thank God i read your post on “what not to say…” for i was about to something probably wrong.

Thank you

It’s definitely a learning process but I thank you for your candor, Vera 🙂 Always try to ascertain the patient’s level of comfort with you and I am sure it will be a good compass on what they feel willing to receive or to share, and of course, be a gauge as to what you can ask.